# A tibble: 1 × 1

prediction

<chr>

1 strawberryWeek 12

Machine Learning in

Python

Soci—269

A Very Gentle Introduction–

November 17th

Reminders

You have a bit more time with

the second coding assignment.

Reminders

Second Coding Assignment Soft Deadline

Your second coding assignment is due by 8:00 PM on Friday, November 21st.

This is a soft deadline.

Reminders

Second Coding Assignment Hard Deadline

All coding assignments (in Python ) must be submitted by 8:00 PM on Wednesday, December 3rd.

Reminders

An Update

Final Presentation and Term Paper

What is Machine Learning?

Some Concrete Definitions

Grimmer and colleagues (2021:396, EMPHASIS ADDED)

A class of flexible algorithmic and statistical techniques for prediction and dimension reduction.

Molina and Garip (2019:28, EMPHASIS ADDED)

A way to learn from data and estimate complex functions that discover representations of some input (X), or link the input to an output (Y) in order to make predictions on new data.

Supervised Machine Learning (SML)

High-Level Overview

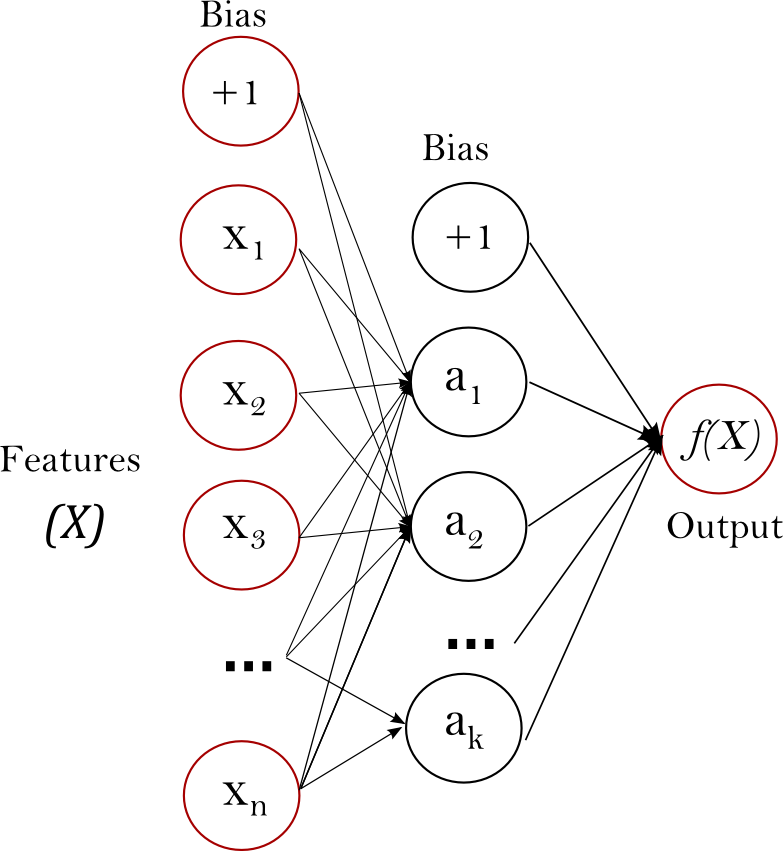

Once deployed, SML algorithms learn the complex patterns linking X—a set of features (or independent variables)—to a target variable (or outcome), Y.

The goal of SML is to optimize predictions—i.e., to find functions or algorithms that offer substantial predictive power when confronted with new or unseen data.

Examples of SML algorithms include logistic regressions, random forests, ridge regressions, support vector machines and neural networks.

A quick note on terminology

If a target variable is quantitative, we are dealing with a regression problem.

If a target variable is qualitative, we are dealing with a classification problem.

Supervised Machine Learning (SML) cont.

An Illustration

# A tibble: 80,000 × 6

fruit shape weight_g colour texture origin

<chr> <chr> <dbl> <chr> <chr> <chr>

1 apple spherical 150 red crispy china

2 banana curved 120 yellow creamy ecuador

3 orange spherical 148 orange juicy egypt

4 watermelon spherical 4500 green juicy spain

5 strawberry conical 13 red juicy mexico

6 grape spherical 5 green juicy chile

7 mango ellipsoidal 240 yellow juicy india

8 pineapple conical 2100 yellow juicy costa rica

9 apple spherical 140 green crispy usa

10 banana curved 110 yellow creamy ecuador

# ℹ 79,990 more rows# A tibble: 1 × 6

fruit shape weight_g colour texture origin

<chr> <chr> <int> <chr> <chr> <chr>

1 <NA> conical 6 red juicy china # A tibble: 8 × 2

fruit probability

<chr> <dbl>

1 apple 0.03

2 banana 0

3 orange 0.05

4 watermelon 0

5 strawberry 0.71

6 grape 0.21

7 mango 0

8 pineapple 0

Unsupervised Machine Learning (UML)

High-Level Overview

UML techniques search for a representation of the inputs (or features) that is more useful than X itself (Molina and Garip 2019).

- Put another way, UML algorithms search for hidden structure or latent patterns in high dimensional space.

In UML, there is no observed outcome variable Y—or target—to supervise the estimation process. Instead, we only have a vector of inputs to work with.

The goal in UML is to develop a lower-dimensional representation of complex data by inductively learning from the interrelationships among inputs.

- This can be achieved by reducing a vector of features to a smaller set of scales—e.g., via principal component analysis—or partitioning the sample into a small number of unobserved groups (e.g., via k-means clustering).

Unsupervised Machine Learning (UML) cont.

An Illustration

| V-Party Name | Label | Underlying Question |

|---|---|---|

v2paanteli |

Anti-Elitism | How important is anti-elite rhetoric for this party? |

v2papeople |

People-Centrism | Do leaders of this party glorify the ordinary people and identify themselves as part of them? |

v2paculsup |

Cultural Chauvinism | To what extent does the party leadership promote the cultural superiority of a specific social group or the nation as a whole? |

v2paminor |

Minority Rights | According to the leadership of this party, how often should the will of the majority be implemented even if doing so would violate the rights of minorities? |

v2paplur |

Political Pluralism | Prior to this election, to what extent was the leadership of this political party clearly committed to free and fair elections with multiple parties, freedom of speech, media, assembly and association? |

v2paopresp |

Demonization of Opponents | Prior to this election, have leaders of this party used severe personal attacks or tactics of demonization against their opponents? |

v2paviol |

Rejection of Political Violence | To what extent does the leadership of this party explicitly discourage the use of violence against domestic political opponents? |

Unsupervised Machine Learning (UML) cont.

An Illustration

Karim and Lukk’s The Radicalization of Mainstream Parties in the 21st Century

Machine Learning vs Classical Statistics

The Two Cultures

As Grimmer and colleagues (2021) note, “machine learning is as much a culture defined by a distinct set of values and tools as it is a set of algorithms.”

This point has, of course, been made elsewhere.

Leo Breiman (2001) famously used the imagery of warring cultures to describe two major traditions—(i) the generative modelling culture and (ii) the predictive modelling culture—that have achieved hegemony within the world of statistical modelling.

The terms generative and predictive (as opposed to data and algorithmic) come from David Donoho’s (2017) 50 Years of Data Science.

The Two Cultures cont.

| Quantity of Interest | Primary Goals | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generative (i.e., Classical Statistics) | |||

| Inferring relationships between X and Y | Interpretability; emphasis on uncertainty around estimates; explanatory power | Bounded by statistical assumptions, inattention to variance across samples | |

| Predictive (i.e., Machine Learning) | |||

| Generating accurate predictions of Y | Predictive power; potential to simplify high dimensional data; relatively unconstrained by statistical assumptions | Inattention to explanatory processes, opaque links between X and Y | |

Note: To be sure, the putative strengths and weaknesses of these modelling “cultures” have been hotly debated.

The Affordances of Machine Learning

Advances in machine learning can provide empirical leverage to social scientists and sharpen social theory in one fell swoop.

Lundberg, Brand and Jeon (2022), for instance, argue that adopting a machine learning framework can help social scientists:

- Amplify human coding

- Summarize complex data structures

- Relax statistical assumptions

- Target researcher attention

While ML is often associated with induction, van Loon (2022) argues that SML algorithms can help us deductively resolve predictability hypotheses as well.

- What plays a larger role in shaping human behaviour—nature or nurture?

Key Terms and Concepts in the SML Setting

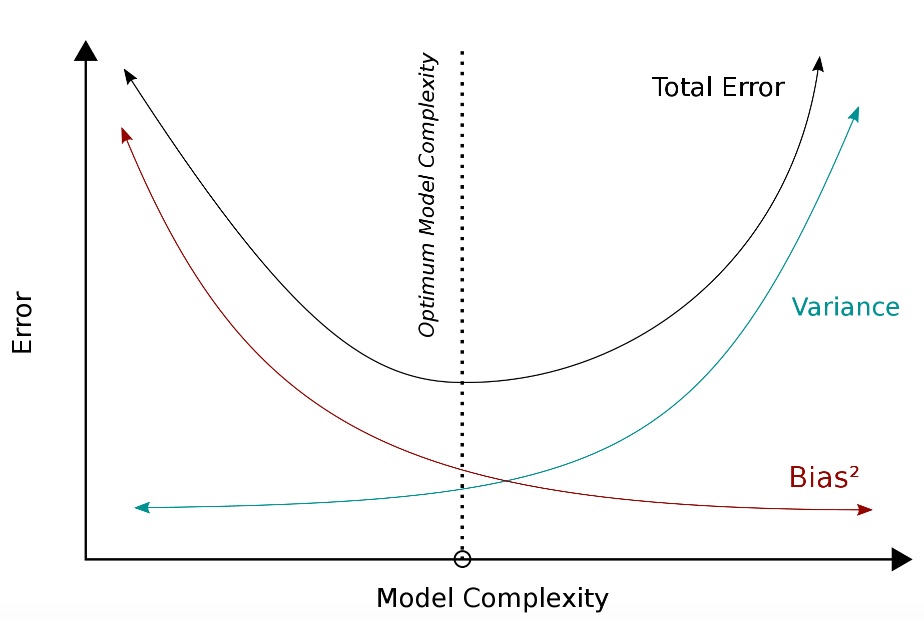

Bias-Variance Tradeoff

Image can be retrieved here.

Bias emerges when we build SML algorithms that fail to sufficiently map the patterns—or pick up the empirical signal–linking X and Y. Think: underfitting.

Variance arises when our algorithms not only pick up the signal linking X and Y, but some of the noise in our data as well. Think: overfitting.

When adopting an SML framework, researchers try to strike the optimal balance between bias and variance.

Training, Validation and Testing

- In an SML setting, we want to reduce our algorithm’s generalization or test error—i.e., “the prediction error of a model on new data” (Molina and Garip 2019).

- To arrive at an estimate of our model’s performance, we can (randomly) partition our global sample of observations into disjoint sets or subsamples.

We can use a training set to fit our algorithm—to find weights (or coefficients), recursively split the feature space to grow decision trees and so on.

Training data should constitute the largest of our three disjoint sets.

We can use a validation set to find the right estimator out of a series of candidate algorithms—or select the best-fitting parameterization of a single algorithm.

Often, using both training and validation sets can be costly: data sparsity can amplify variance across samples or datasets.

Thus, when limited to smaller samples, analysts often combine training and validation—say, by recycling training data for model tuning and selection.

We can use a testing set to generate a measure of our model’s predictive accuracy (e.g., the

F1 scorefor classification problems)—or to derive our generalization error.This subsample is used only once (to report the performance metric); put another way, it cannot be used to train, tune or select our algorithm.

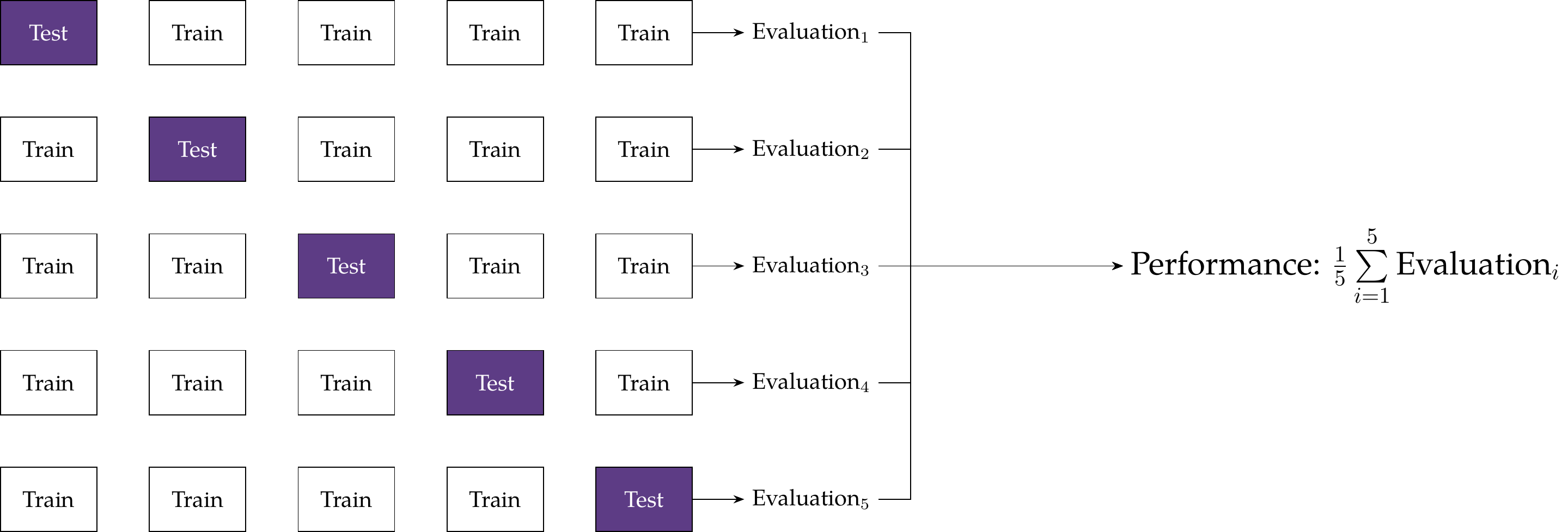

k-Fold Cross-Validation

Unlike conventional approaches to sample partition, k or v-fold cross-validation allows us to learn from all our data.

k-fold cross-validation proceeds as follows:

- We randomly divide our overall sample into k subsets or folds.

- We train our algorithm on k - 1 folds, holding just one group out for model assessment.

- We repeat this process k times—every fold is held out once and used to fit the model k - 1 times.

- We then pool or average the evaluation metrics (e.g., predictive accuracy) for all the held-out runs.

Stratified k-fold cross-validation ensures that the distribution of class labels (or for numeric targets, the mean) is relatively constant across folds.

Hyperparameter Optimization

In SML settings, we automatically learn the parameters (e.g., coefficients) of our algorithms during estimation.

Hyperparameters, on the other hand, are chosen by the analyst, guide the entire learning or estimation process, and can powerfully shape our algorithm’s predictive performance.

- Examples of hyperparameters include the k in nearest neighbours models, the \alpha penalty term in ridge regressions, or the number of hidden layers in a neural network.

How can analysts settle on the right hyperparameter value(s)?

- Test different values via trial and error.

- Use automated procedures like

GridSearchCVfromscikit-learn.

k-Nearest Neighbours

Brief Overview of KNN

k-nearest neighbours (KNNs) are simple, non-parametric algorithms that predict values of Y based on the distance between rows (or observations’ inputs).

The estimation of KNNs proceeds as follows:

- The analyst defines the distance metric (e.g., Euclidean, Manhattan) they will use to determine how similar any two observations are based on their vector of features.

- The analyst defines a value for the hyperparameter k—that is, the number of nearest neighbours to find in the training subsample.

- When fed a new data point, KNNs find the k nearest neighbours in the training data, and:

- Assign the new observation to the class that most of its k nearest neighbours belong to (for classification problems.)

- Generate a prediction of Y by taking the average of the target variable for the new observation’s k nearest neighbours (for regression problems.)

- Assign the new observation to the class that most of its k nearest neighbours belong to (for classification problems.)

KNN in Python

Note

The rest of today’s session will take place in Colab.

An Open Work Session–

November 19th

Reminders

You have a bit more time with

the second coding assignment.

Reminders

Second Coding Assignment Soft Deadline

Your second coding assignment is due by 8:00 PM on Friday, November 21st.

This is a soft deadline.

Reminders

Second Coding Assignment Hard Deadline

All coding assignments (in Python ) must be submitted by 8:00 PM on Wednesday, December 3rd.

Reminders

Reminders

Final Presentation and Term Paper

Reminders

You can find out when you’re presenting

via Moodle.

An Update

A quick note on grades—and an opportunity for resubmitting or

re-weighting a coding assignment.

Work Session

Create a Pitch

Carefully review the guidelines for your term paper: i.e., scan the codebooks—or leverage the interactive tables—embedded online to isolate variables of interest. How can you connect these items to the substantive material covered in Module I of this class?

Towards the end of class, we’ll hold a brainstorming session where everyone will pitch their preliminary ideas.

Enjoy the Break

References

Note: Scroll to access the entire bibliography